Tokelau Language Standards

Ko te tamaiti – te pūtake o te kaupapa

The child – the heart of the matter

The following are Matāeke o Akoakoga’s guidelines for writing and recording text for teaching and learning resources published in gagana Tokelau and English.

Introduction

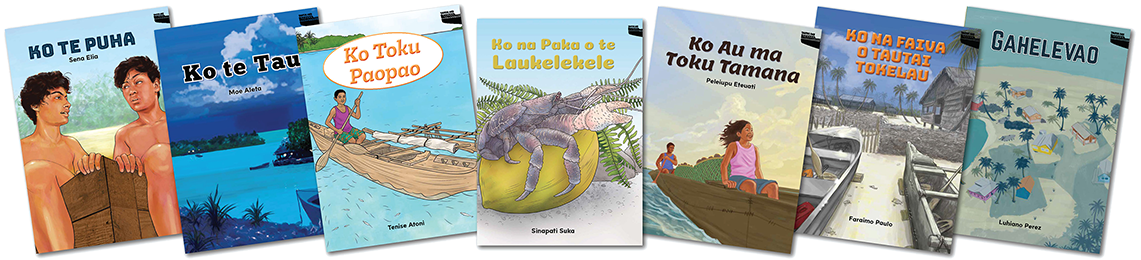

Matāeke o Akoakoga (the Tokelau Department of Education) is publishing Tokelau language resources for schools in a series called Tautai Ake. The Australian Government has committed AUD1,200,000 to the development of these resources over a number of years. The establishment of a Tokelau Language Commission is a work in progress during this time.

In order for the resources to be developed in a quality-assured way, Matāeke of Akoakoga has established a systematic approach to translation and word creation and has created language guidelines and quality-assurance structures involving a language resources committee, writers, translators, and moderators. The establishment of the Commission will provide the mechanism to confirm and progress the work on Tokelau language guidelines and standards.

Matāeke o Akoakoga a Tokelau provides these guidelines for anyone involved in the production of learning resources intended for students attending school in Tokelau and the resources for teachers that accompany them. These guidelines are informed by:

- the Tokelau national curriculum policy framework Takiala Kautu o na Polokalame Akoako a Tokelau (2006)

- curriculum statements for Tokelau, English, mathematics, science, social sciences, health, and physical education

- the Education Review Office report, National Evaluation of Education Provision in Tokelau (2014)

- research into the teaching of reading conducted by Matāeke o Akoakoga (2014).

Matāeke of Akoakoga advises that:

- a key learning outcome of Takiala Kautu o na Polokalame Akoako a Tokelau is that every student in Tokelau will become bilingual and biliterate in both gagana Tokelau and English

- biliteracy encompasses an understanding of a range of oral forms and text types

- English is only included informally before Year 3

- gagana Tokelau is the main medium of instruction from early childhood to Year 7 – and thereafter is a medium of instruction for 50% of the curriculum to Year 11

- gagana Tokelau is the medium of instruction for 80% of the curriculum in Year 3, gradually decreasing to 50% by Year 7.

Language issues

Mekelono (macrons)

Historically, text printed in gagana Tokelau has taken two forms:

- a version that includes macrons

- a version that includes macrons only where a fluent speaker would not be able to tell which of two otherwise similarly-spelled words is intended, relying solely on the context.

When Loimata Iupati was the Director of Education, Matāeke o Akoakoga conducted research into learning how to read, comparing reading progress in junior classes by children learning how to read with text printed in gagana Tokelau that did – and did not – incorporate macrons. Children learning how to read with text that incorporated macrons made better progress in learning how to read. The inclusion of macrons provides students with a grapho-phonic source of information.

A further advantage of incorporating macrons into printed text is alignment with the Tokelau Dictionary (1986), which uses macrons. However, whereas the dictionary deals with words in lists and guides pronounciation as well as provide meaning, the Tokelau language resources are sustained (running) texts in which the context provides another important source of information to work out which form is intended.

Matāeke of Akoakoga therefore provides the following detailed guidelines for the use of macrons in printed teaching and learning resources. Rather than use the Tokelau Dictionary as a guide:

- Don’t include macrons in single- and two-letter words unless the meaning is ambiguous – but when a two-letter word consists of two vowels, use macron(s) to show the intended meaning and stress, for example, uō.

- Don’t include macrons where the pronunciation is widely known.

- Leave the macron off when a speaker can say a word either way (for example, tamana or tamanā).

- Include macrons where the meaning would otherwise be ambiguous.

- Whether and where a word such as totoga has macrons depends on what follows. For example, when followed directly by a noun, for example, totōgā mauteni, totōgā niu, totōgā lakau – but when followed by a noun phrase, i te totōga o na fatu mauteni.

- Once a word is macronised in published resources, retain macron(s) in the same word in subsequent publications, for the sake of consistency.

Gagana fakapitonuku (dialect) and hikuleo (accent)

While printed and spoken gagana Tokelau can reflect vocabulary and accent (intonation) differences between the gagana Tokelau spoken in the Atafu, Nukunonu, and Fakaofo communities, these differences are becoming less apparent with each generation. Listening to the spoken language of a young person, for example, it is no longer always easy to tell which atoll they come from.

Principles of word-creation

We need to take a systematic approach to word-creation to ensure that our language flourishes and survives into the future. A number of word-creation strategies are possible. The creation of new words for Matāeke o Akoakoga’s Tautai Ake resources uses several, depending on their suitability for the learning context and the potential impact on gagana Tokelau’s status and structures. These strategies include:

- using a phrase (a group of words) as an explanation, for example, autumn – tau e malili ai lau o lakau; spring – tau tuputupu; atoll – motu akau; solar energy – malohiaga uila mai te la; renewable energy – malohiaga maua tumau e maua mai i na lihohi fakanatula, (e ve ko te malama o te la, matagi, ma te huavai e mafai ona toe fakafōu pe fakatumu fakate natula) or malohiaga maua tumau e mafai ona fakafougia faka-te-natula or malohiaga fakafougia

- creating a new word by putting words (or parts of words) together, for example, fringing reef – akautafatafa; barrier reef – akaupuipui; windmills – pekapeka matagi

- extending the meaning of an existing word to cover a new meaning, for example, uila – lightning; electricity (so uila-eletihe – electric lighting)

- taking a word from another language and using it, without changing it, in gagana Tokelau, for example, piano, Greenland, Samoa

- forming a new word by fakapipiki (affixation), for example, using the prefix faka-, as in fakaeletihe and fakafougia; and using the suffix -gia, as in fakafougia

- transliterating – taking a word from another language and making it sound like a word in gagana Tokelau, for example, by changing or adding vowels, as in key – ki; cooler – kula; power – paoa; carbon dioxide – kaponi taiokihite.

Base your choice of strategy on an analysis of the likely impact on the status of gagana Tokelau, the development of the language, the ease of communication between everyone involved, and the capacity of the new word to capture the essence of the original meaning. Avoid transliteration if another strategy provides a natural, clear, and easy-to-understand alternative. And avoid the overuse of borrowed words from other languages (where the word remains unchanged), for example, photosynthesis and phytoplankton, as this could affect how students view our language. Students could mistakenly conclude that gagana Tokelau is word-poor. Overuse of transliterations and kupu kopi (borrowed words) can even render text incomprehensible, affect language attitudes, and leave students preferring resources published in English. Never-the-less, some transliterated words have become so common that they are accepted, for example email – imeli and internet – initaneti.

If you follow these principles of word-creation, you will be helping to ensure that we take a systematic approach to the advancement of gagana Tokelau.

Establishing new words

The creation of new words is only the beginning stage of three general processes that lead to the establishment of words in the language. The continuum from first use to establishment generally has three stages: creation, consolidation, and establishment. Through using the resources, the new words in them will gain wider acceptance and become familiar to more and more speakers. In this way, their form and meaning will stabilise as part of the Tokelau lexicon (vocabulary).

The deliberate focus on science texts, in particular, achieves two purposes. The first is to advance the language through new words and concepts being available to speakers. The second is to facilitate learning science in gagana Tokelau. Using the resources in schools and homes leads to the establishment of words in our language.

Wh

Before 1974, the sound represented by the letter “f” was sometimes written as “wh” or “h”. At the 1974 Fono Fakamua, the Tokelau community agreed that “f”, rather than “wh”, would be used thereafter. The Tokelau Dictionary

(1986) therefore uses the “f” spelling.

Alternative spellings and pronunciations

Where there are alternative ways to spell and pronounce a word, for example:

- vehea / vefea

- taigole / tainole / taikole

for the sake of consistency and to avoid confusing younger children when they are learning how to read, stick to one spelling. With older students, gradually ensure that they are familiar with the alternatives.

Style guide

Like any other publisher, Matāeke o Akoakoga has developed a style guide. Here are some issues of style to consider.

Alphabetical order

Gagana Tokelau is written with a fifteen-letter alphabet. The Tokelau Dictionary, published by the Office of Tokelau Affairs, applies the following alphabetical order:

a, e, i, o, u, f, g, k, l, m, n, p, h, t, v.

Capital letters

Capitalise La (the Sun) and Mahina (the Moon) in astronomical contexts, but otherwise use lower case (la and mahina).

Notice the difference between “and his mum arrived” and “and Mum arrived”.

Avoid over-capitilisation, for example, “Matāeke o Akoakoga” not “Matāeke O Akoakoga” and (in running text) “gagana Tokelau rather than “Gagana Tokelau” (as in “both the English language and gagana Tokelau are mediums of instruction from Year 3 onwards”).

Kamatagakupu (prefixes) and fakaikugakupu (suffixes)

Avoid adding English prefixes and suffixes to Tokelau words in text in English, so “Tokelau” rather than “Tokelauan” and “three fale” rather than “three fales”.

Kupu fakaali and kupu kalama (grammatical words)

A kupu (word) is a sequence of sounds and letters that has a meaning and function. It can exist on its own and still make sense. Words that just perform grammatical fuctions include one- and two-syllable words, such as te, ni, he, ki, i, o, ko, na, e, nae, and kua. Their meaning can only be understood in the context of the words around them. With such words in written text, apply the following guidelines:

- Grammatical words are words in their own right, so write them as separate words.

- It is misleading to combine a grammatical word and the noun or pronoun it refers to, for example, to write kilatou, kimatou, kitatou, kilaua, kitaua, kite, kote, ite, ehe, and so on. This is misleading because these are separate words – so write:

ki latou, not kilatou

ki matou, not kimatou

ki tatou, not kitatou

ki laua, not kilaua

ki maua, not kimaua

ki taua, not kitaua

ki te, not kite

ki ona, not kiona

ki ana, not kiana

ki tona, not kitona

ki a, not kia (as in “ki a Mele”)

ki ei, not kiei

ko tona, not kotona

ko te, not kote

ko na, not kona

e he, not ehe.

But note, for example, that “kite” isn’t a grammatical word when it means “to look for”, as in “Fano oi kite mai toku kofu.”

Fuainumela (numerals) and numela (numbers)

In running text, spell out one (tahi) to ten (hefulu, if people), but then use numerals.

Use numerals straight away with measurements, for example, “7 kilomita”.

Serial comma

Use a serial comma to avoid ambiguity, as in the sentence, “She emailed her parents, Hatesa, and Fuimanu” (where she is sending an email to four people). “She emailed her parents, Hatesa and Fuimanu” implies that she sent an email to two people (whose names were Hatesa and Fuimanu).

Nauna fakapitoa (proper nouns)

Allow individuals and organisations to spell their names (and apply macrons in them) as they prefer, for example:

- Ēliu Faamāoni (personal preference)

- Lepeka Amato Tovio – not Tōvio (personal preference)

- Lift Education E Tū (organisation’s preference)

- Matāeke o Akoakoga (Department of Education’s preference).

For the names of countries, use “Auhetalia” for “Australia” and “Niu Hila” for “New Zealand”. Write “Samoa” (not “Hamoa”) in a postal address.

References

Hopper, Robin (1993). Studies in Tokelauan Syntax. Auckland: University of Auckland [thesis].

Hopper, Robin (1996). Tokelauan. Munich: Lincom Europa.

Iosua, Ioane and Braumont, Clive (1997). An Introduction to the Tokelauan Language. Auckland: Clive H. and Daisy J. M. Beaumont.

Hovdhaugen, Even (1989). Ko te Kalama Tokelau Muamua. Oslo: Aschehoug.

Hovdhaugen, Even; Hoëm, Ingjerd; Iosefo, Consulata Mahina; and Vonen, Arnfinn Muruvik. (1989). A Handbook of the Tokelau Language. Oslo: Norwegian University Press and Apia: Office of Tokelau Affairs.

Ministry of Education (2009). Gagana Tokelau: The Tokelau Language Guidelines. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education (2011). Muakaiga! An Introduction to Gagana Tokelau. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Simona, Ropati (1986). Tokelau Dictionary. Apia: Office of Tokelau Affairs. [www.thebookshelf.auckland.ac.nz/docs/TokelauDictionary]

Sharples, Pita (1976). Tokelauan Syntax in the Sentence Structure of [a] Polynesian Language. Auckland: University of Auckland [thesis].

Vonen, Arnfinn Muruvik (1999). “Negation in Tokelauan” in Negation in Oceanic Languages. Munich: Lincom Europa.